One Scholastic Book Fair I spent my contentiously negotiated book fair allowance on “The Maze of Bones”, the first book in the 39 Clues series. It slightly changed my life, as every book does at that age. The main characters discover they are members of the most influential family in history, and embark on a globetrotting quest to find the Clues, which are infused with the aforementioned history. The first book, set in Paris, has them find the Clue in the catacombs. So then I got mildly obsessed with the catacombs.

Like every kid who proudly speedread Harry Potter in fourth grade February and still does not shut up about it, I desperately awaited mysterious men who would approach me to announce that I am a wizard. But even then I knew this was a bit unrealistic. I decided that the 39 Clues thing, mysterious men who would tell me I’m part of the most influential family in history, might do. Or, at the very least, someone — they didn’t even have to be mysterious, though in the end, isn’t everyone? — to confirm my deep-seated and obviously evidenced conviction that I was somehow, in some way, not totally unimportant.

I wanted so very much to go on adventures, like the children in my series, Magic Tree House, Percy Jackson, Redwall, Kingdom Keepers, Secrets of the Immortal Nicolas Flamel. Everything I had ever seen taught me that this is how the world works: one must go on an adventure; one must narrowly and variously escape death or at least boredom; one must save one’s co-adventurer’s life; one thereby earns a kiss.

The semester following a breakup (coincidentally! I swear!) I went to Paris for study abroad. I needed to go to the catacombs. I even wrote it down, in the goals file I kept in Emacs.

So I dragged my friends to the official catacombs tour. We talked excitedly about what we might find, preemptively mythologizing our quest. “I wonder if we can go off-trail,” we said to each other. “I wonder if people ever get lost.” I talked like I knew something: “There’s raves down there. They connect into natural caverns. Sometimes the ceilings fall. You can enter them via subways.”

“There’s raves down there?” a friend asked. “How do you know that?”

“The Internet,” I said.

After the modern preamble with historical background that I was the only person boring enough to read, after the limestone quarry tunnels which, I knowingly explained, were excavated to build Paris, and after someone replied, “Bro, I know, we literally talked about that in class last week”, we finally arrived at the antechamber to the catacombs proper. Above an open gate hung the famous sign: “ARRÊTE! C’EST ICI L’EMPIRE DE LA MORT”, or “Stop! This is the empire of death”.

The initial impression is incredible. It silenced me. (And it takes a lot to do that.) I mean, how often do you see a human skull? How often do you see hundreds or thousands of them? Arranged neatly into lines, patterns, and even hearts?

We passed through hallways lined with bones. Because they’re so geometric, so organized, some sort of abstraction happens. It’s hard to see a femur as having belonged, maybe, to Jean, the village weirdo, or to Marie, the one who got fed up with Jean and sent him here. Slowly, they turn from human remains into so much decoration. They look fake. Like that house that goes overboard on Halloween every year.

I noticed my eyes glazing over, passing over at a glance what a hundred souls left behind, and I stopped myself, and stared at a skull. I imagined myself the Prince of Denmark. It was small. Maybe a child’s. There was a crack in it. I stared into the voids of the eye sockets, and I tried to recapture, or maybe capture anew, the feeling from which I had dissociated — had I indeed felt it? — the feeling that I knew I was supposed to have in front of all these skulls, wasn’t that was I was feeling now, the canonical, the novelistic, the poetic response to the death that has undone so many?

It reminded me of when I was on a death kick in high school, as teenagers often are. I raced cyclocross at the time, and I fancied it dangerous. I wrote in Sharpie on my bike “MM”; I wrote in the inside of my deployant watch clasp “MM”. I thought it was apt, you know, since it’s a watch. Time, and all that. People would look at it and they’d say “Ha, nerd. And you forgot the third W.”

A million deaths a statistic, and a million femurs even more. I leaned my hip against a wall of hips and checked my phone, forgetting there was no service. I saw the light-cone of someone’s flash illuminate a corner of the dust to which we shall return, the picture destined for Instagram.

Despite the fact that I made everyone wait so I could read the explainer panels, it was only after we left that I learned that these catacombs — the part open to the public, the part we were touring — were built expressly for tourists. And so we were.

I heard American English. There’s nothing worse than hearing American English, as an American, in Paris. First, it ruins the vibes, you might as well slap a McDonald’s and a Gap down right there. But also, you feel somehow outed, you feel like someone will somehow recognize you too as a hayseed American and lump you in with those guys, those of the shorts and the flip-flops and the graphic shirts and the children on leashes. Anything but that, no, I am Asian, I speak French even, and I cringed behind some bones, and then remembered, You’re supposed to be thinking about death! Literally the opposite of caring how you’re perceived! Literally the point of these skulls! Get it together!

All that time that nagging sensation, respect this, think about it, every two tibia a human being. At the very least have enough respect for yourself to Experience Culture. The corridors with plaques inscribed with snippets from the Vulgate and stanzas from French poetry, they who tell you what to feel.

In the end the bones aren’t death, they can’t be death, since these walls, built in the insane Revolution rationality expressly for tourists, are too much reason, and there is still too much halogen light that your tickets paid for, and there are too many people speaking too much English, and you laugh and you joke with your friends, in English, and at the end you go blinking into the day to find a bite to eat. At McDonald’s, perhaps.

The next day, I happened to be hanging out with them again. One of my friends, Charlie, had been recommended a bar, from two separate people, and we decided to go there.

As it was Paris, and as they were cheap, and as I imagined one must, I permitted myself to go to bars. In fact I sought them out. Whenever I travel, I read about the city. At a minimum, I read its Wikipedia page. But for such a special occasion as Paris, I spent the entire summer reading everything I could get my hands on. And I knew, from this reading and also from my general francophilia, that in the old Paris, in fact in the halcyon world that tragically ended the minute I was born, the one that I so earnestly mythologized from my podunk contemporary America, bars and cafés were third places, where people knew your name, where you would go to simply be.

I wanted to go to such bars. I wanted to go to the bars for philosophers, for revolutionaries, for Sartre, for poets manqués, for romantics darkly scribbling in their notebooks in the corner. Bars with a theme, with a sujet. But no, I told myself, no, you bookblind boy, that is the old halcyon world, the one that ended the minute you were born; today there is only the same bar, the one in “The World’s End”, living off the interest on the endowment of the past, and nowhere is that patrimoine larger, and more parasitically ransacked, than in Paris.

So we went to a bar. I saved us seats at the community table, which was recessed and circumscribed by a bench, and observed carefully. I prided myself on my observation skills. Like Sherlock Holmes.

When my friends got back with drinks, I said to them, my eyes flicking between theirs at like forty hertz, the way that they do when I’m excited, “Guys. Guys. This was a sex hotel!”

“Um, okay…,” someone said.

I pointed, a grin disfiguring my face, to an old wooden sign, surely original, that hung above the stairs down to the basement bathrooms. “BAR,” it read, “CHAMBRES À L’HEURE”. Rooms by the hour.

Just then, pleased by my noticing — look at me now Colleen, I thought, the professor I had frequently frustrated by my failure to “close read” — a man sitting near us turned to talk to us. He was tall, and his complexion, pale and yet dark, pallid-somber, reminded me of a skeleton. His name was, incredibly, Cobalt Balthazar.

“So, you like the catacombs?” he said. I was taken aback. After all, we’d just been there yesterday. And to tell the truth, I’d kind of given up on my dream already, after seeing the museum; I thought to myself that this is one of the Forbidden Hopes; I, totally normal I, unexciting I, Ohio I, would never enter into such a sacred hidden place.

“Yeah! I do!” I said. “Do you like the catacombs?”

He chuckled at my ignorance. “Yes. I like the catacombs. Everyone here does.”

“Oh,” I said.

“This is a catacomb bar,” he said.

“Oh. Wait. Huh?”

“This is a catacomb bar. Look around. Everything you see here — every single last thing — is about the catacombs. This,” he said, pointing above us to the ceiling of the pagoda that sheltered the community table, which hosted a hitherto abstract fresco, “is from the catacombs. That graffiti is from the catacombs. Those pictures are from the catacombs. Everyone here is from the catacombs. They are cataphiles. How did you come here? Nobody comes without knowing. Nobody.”

I couldn’t believe it. I thought I’d grokked the place in a single eye. Sure, I’d noticed the rather eclectic decor, climbing gear, antique lamps, but I thought that was like some sort of hipster thing. I looked around afresh. I noticed a party of three, making their way to the back of the bar: an Italian looking man, in his mid-fifties, in a gray woolen mobster suit, the first two buttons of his dress shirt unbuttoned, behind him a man of unknowable race in a multicolored Rasta hat wearing a big flowy yellow robe, behind him a thirtysomething Black woman, impeccably dressed in officewear, a navy blazer over a black turtleneck with light wash jeans.

I daggered Charlie with my eyes blazing and I demanded of him: “Did you know.”

“Did I know what?”

“That this is a catacomb bar!”

“No, chill.”

I was incredulous. What were the chances? That I’d stumble into a cataphile bar, the very day after we went to the tour?

Balthazar went on. “On Tuesdays and Fridays, everyone is a cataphile here. Everyone who is leaving, they are descending. That is why they are saying to each other Au-dessus. They will meet later, underground.”

“Can you take us?” I said already. He said he’s not going tonight, and asked me if I had an Instagram or a Telegram. I have none of the grams! It is my principled stand against American technohegemony, it is my Individualistic Résistance, it is my Not Of This World, it is my — no, that all went out the window. I will make one, I said immediately.

Balthazar wrote his handles in my phone. “If you crave for catacombs,” he wrote.

I craved. I craved! “Tell me everything,” I said, by everything I had in me. I stared into his eyes, his deep, sleepy, soulful eyes, listening closer than I’d ever listened.

“Are you afraid of the police?” I asked.

“The police, they sleep,” he said, authoritatively and nonchalantly. “If you are not African or Arab, they do nothing.”

“What else do you like?”

“All sorts of things. Lock-picking. Painting, graffiti and oil. Drawing, making photos. Making keys.”

“Making keys?”

“We make keys to restricted places.”

“Do you sell them then?”

“Never. We distribute them, we collect them.”

I watched him get up, pretty drunk, and take a black paint pen out of his pocket. He shook it three times, uncapped it, and in easy, confident, elegant precision, added two perfect graffiti to the wall.

“Is that your tag?” I asked.

“Nah, I just made it up.”

“Where can I see your graffiti work?”

“Bah, everywhere. Look on the ceilings in the tunnels of the métro. I paint insects on the ceilings; I abseil and I paint.”

“You’re not afraid?”

“Painting in the métro, if they catch you, it’s a 350,000 euro fine, and sometimes a year in jail. But I’m careful. I wear a mask and I go at night.”

“Why do you do this?”

“I can’t really explain it,” he said, and then switched to French. “You can’t know it except by living it. It’s like — it’s like how if you taste LSD, you can’t explain it. It’s harder to explain that that even.”

Starry-eyed, I said “Yes. It must be ineffable. Ineffable? Is that a word in French?” I adopted my accent. “Ineffable. Indisable?”

“Yes,” he said, laughing, “it’s a word. But few French people know that word.” (Now he will like me, I thought. I know a word that few know.)

“How did you get started?”

“After I got kicked out of high school, my friends and I started to explore an abandoned chateau next door. We put locks on the doors. We painted it. We looked for other abandoned places, places to explore.”

“How old were you?”

“Fourteen,” he said.

“Do you climb?” I asked.

“Many of us climb.” Finally, something I do too. He continued: “People climb the churches, but I’m not strong enough for that.” A different kind of climbing than my yuppie indoor bouldering.

A seventeen-year-old law student named Charles — law, in this den of anarchists! — said that he was into climbing. He showed me his Instagram.

“That’s me on a crane,” he said, “and on a church, and on another building. That’s me on the Louvre.”

“The Louvre? The Louvre??”

He said, in French, “If one has good operations, one can go any place. There are no closed doors.” He pointed at a skylight in the picture. “That window, it’s not locked. One could descend. I didn’t descend, because if you descend, it gets a bit hot,” implying “with the police”.

A bit hot! Breaking into the most secure museum in France, the most iconified museum in the world, a bit hot! I laughed and said, “You, you’re like Lupin. You’re like Arsène Lupin.”

I looked around and now I could clock it. That vibe — that burr, that edge — that spirit of anarchism. That spirit of breaking the rules, just for breaking the rules. People knew each other, they were bonded by being on the other side of the law, the barmen called people amis, “Amis, could you move inside, please.”

While I was interviewing Balthazar an old man sat at the table that overlooked ours and started to talk to Charlie. (Charlie later said, “I thought he was a creep. I kept shooting you guys glances to get me out of there. But then he — did you see?? — he started showing me maps.”) I did see. For the next thing you know, this old man, grizzled, white hair and beard, wearing caving gear, was sitting next to Charlie, showing him a binder full of mimeographed catacombs maps. I was entranced. I couldn’t believe it. The old man’s name was Tristan. (Like Tristan and Isolde, I thought to myself.) As he was leaving he said, “Do you guys want to come? It’s just that your feet will get wet,” he said, pointing to his waders.

In the nights that followed I wondered if I had made a mistake. I lay awake in bed, imagining Tristan leading me through tunnels with those maps in his hand, imagining what would have happened if I had said yes. Did I want to come? Yes, I wanted to. I wanted to so very much. Or was it that I wanted to want to? I can come up with any number of excuses: it was already late, and I slept at 10:30; I was wearing Vans; I was already overstimulated. But mostly I had not yet learned how to say yes. That’s what Paris was for.

In the weeks that followed, I tried to contact Balthazar and Charles. I had made an Instagram. I sent them DMs to no avail. And I was busy, what with school, touristing, and all that. Every Tuesday and Friday, I would think to myself, Should I go to the bar again. And every Tuesday and Friday, something came up. Usually it was sleep. It would soon be winter, and cold for exploring.

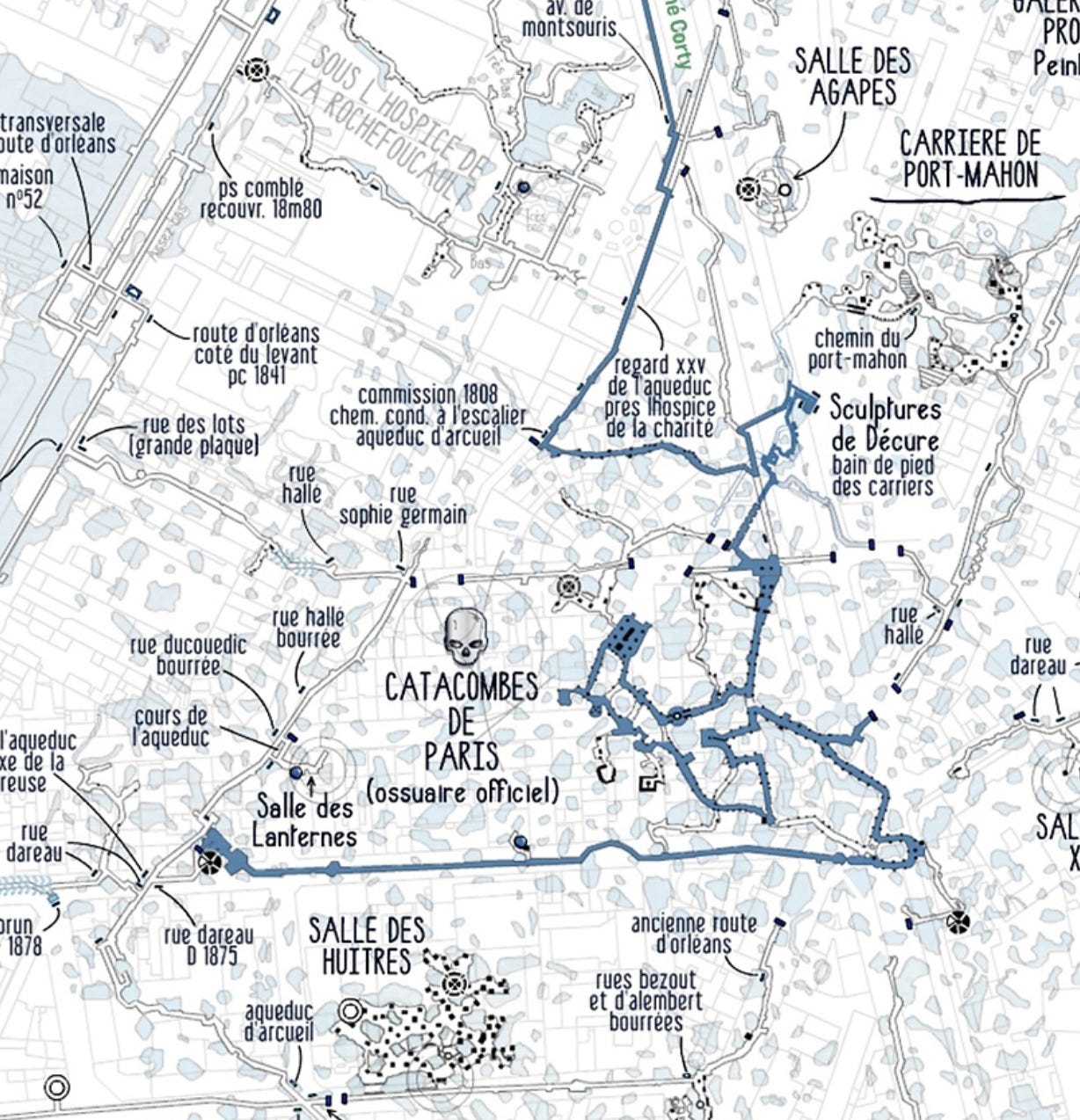

I decided to go on my own. In daylight, to not interfere with my precious sleep schedule. I spent hours scouring the Internet for maps. I wrote a program to crawl an invitation-only cataphile forum which didn’t put media assets behind authentication. I gathered maps; I even, ever the student, skimmed Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project.

Comparing the hand-drawn maps to satellite imagery, I identified two entrances that I would try: one at a church, and one in a park at the south edge of Paris. One Saturday, at noon, I went to the church. It was empty except for the Holy Spirit. The map said the stairs were in a shed. But there was an old man around, and I got the feeling he might be watching me, and anyway maybe God wouldn’t like me trespassing on a church, so I left without trying the door.

I took the tram to the park and I walked around, looking for… something. A sign? That said “Empire of Death, fifty meters ahead”? As I was walking, I saw someone jumping a fence. I waited, and then I jumped it too, and walked along an abandoned railroad, passing through a long dark tunnel, until at the end of it I saw him, and smelled him smoking weed. It was a beautiful place, like a Romantic picture, with vines and old stone and moss.

“Bonjour,” I said. “It’s very beautiful here.”

“Yes.”

“Are you a photographer?” He had a camera.

“Yes.”

“So…” I said, very smoothly. “Do you know where the catacombs are?”

“Yeah, I know. It’s the other way. Follow the railroad until another door, like the one you jumped over to get here. After a long tunnel, you’ll see trash bags, on the left. The cataphiles use them. It’s there. It’s small and deep.”

“Is it hard to enter?”

“It’s pretty narrow. It’s the most well-known entrance, but not the easiest one.”

“What’s the easiest one?”

“There’s holes in the roads.”

“It’s gotta be night then, right?”

“No, it’s Paris, you can do whatever you want.”

And so I walked. The railbed was made of fist-sized stones, slightly too big to walk on comfortably, and the ties were slightly too close together to walk atop. I checked my phone. This was back in the days of yore, the days when I got notifs. The poet whose workshop I was trying to join next semester wrote to let me in, despite my poems “seeming very young”, and I tried not to be offended; my mercurial friend, of whom I had known four personalities by now, was continuing to not do so well, and I was continuing to feel guilty about my continuing to do nothing; I’d been rejected from a job.

Not looking where I was going, I fell into a hole. Dazed, I looked around, and noticed some trash bags. This must be it. I turned on the Petzl headlamp that I’d bought at Décathlon, the French Dick’s, and peered into the hole. Sure enough, a tunnel issued into the wall. It was strait and narrow.

I zipped up my jacket, which was wholly inappropriate for the situation, and crawled into the tunnel, on my hands and feet. After hopping down a shelf, the dirt tunnel changed into a gray limestone corridor, and I was able to sort of waddle. The path ahead was flooded. I knew about the flooding from my research, and I had worn my Bean Boots, though this path was still impassable, the water being a foot deep.

I turned left instead. I remembered another warning that the photographer had given me: “It is necessary to not go left, right, left. It is necessary to know where one is.” And I’m horrible with roads. So after being forced to take another turn, I knew that I was sure to get lost. The photographer did assure me that since it’s a weekend and this is the most well-known entrance, there would be others, but I still worried. I squatted in the tunnel and stared into my phone, whose battery was rapidly diminishing, scrutinizing the map and trying to figure out where I was. I did not succeed.

The Greeks used to think that something from your eyes let you see. (They had trouble explaining why people can’t see in the dark.) But now it was true. I turned off my headlamp, to see what it’d be like, and it was the most profound darkness, the kind that is tangible, the kind that plunges its fingers into your lungs, and I immediately turned it back on.

Despite my best efforts, I imagined getting lost. I imagined days spent wandering the tunnels, licking the water off the walls, dying of hunger, my body eventually rotting in these limestone tunnels, encased, over centuries, by a coffin of calcium carbonate, a human stalagmite. The still air, ghostly dust, the utter silence except for the sound of water dripping in deep time, the weight of a city above you. These tunnels, these tunnels explored by those who knew, these endless identical low tunnels as far as my lamp threw its rapidly gobbled light, these tunnels dug by men whose bones I had seen, these tunnels were a metaparis, and there is no loneliness more profound than the loneliness of Paris.

I usually decide not to be afraid. But without a soul to wear it for, the mask did not convince me.

I smelled them first, and then I saw their lights in the distance. People! I wouldn’t die! It smelled like weed. I hailed them, and then waddled over.

They turned out to be a group of three boys, fifteen years old, smoking. They spoke to me in English; the shortest boy, who had beautiful long blond hair, was fluent. (He said that he goes to an English school, having been expelled from his French one.) They were Russians, and had been in France for nine years. They were kind, and equipped with the myths that are the domain of teenagers. They reported to me that there were killer hobos in the tunnels. They asked, gravely, whether I was armed. What does that even mean in France. I said I have a knife. One of them immediately tried to sell me hash. When I refused, he pivoted to coke. They talked to each other in a mixture of French and Russian, with expletives in English.

“So are you guys cataphiles?” I asked.

“Yes,” one of them said. All three of them relied on their phone flashlights, and had ineffectively tied plastic bags over their sneakers.

“No we’re not,” his friend shot back. “I know the real ones. They showed me a tunnel with a dead man in it.”

“Fucking liar,” the third said.

I said to myself, You can’t abandon these boys, they’re fifteen. What do they know. But really it was I who couldn’t be abandoned.

In the distance, we saw red lights. This got the boys excited. “They’re Satanists,” one declared, “there are Satanists in these tunnels.”

“Oh yeah?” I said.

“Look at how the lights, they’re red, they flicker. They’re not lights, they’re — they’re —” he didn’t know the word for candle — “bougies”. I admit his fear got to me. The tunnels make you afraid. So we sped up.

But the Satanists caught up to us, having surer step, and I didn’t look at them, hoping that then they wouldn’t notice me. I prepared myself to be eaten alive. It turned out that they were just explorers. The one in the front said “Attendez, attendez,” and asked, “C’est vous qui fumez un oinj?” and I said “Quoi?” and they said “A joint. It is you who smokes the joint.” I immediately threw the Russians, my charges, under the Satanist bus. “No, it’s them.” “Okay,” he said, and told them in French that they shouldn’t smoke down here, there’s no ventilation.

We hugged the wall as we let them pass. I watched them go. I saw what they had — headlamps (red, for night vision), backpacks, GriGris, rope, long boots, overalls — I wanted to say, “Attendez, attendez,” I wanted to say, “I am not really with them, these boys, I want to see the catacombs. Where are you going? I want to follow you. I want to see what you have seen.”

But I imagined I had already been besmirched by my association. I imagined, on priors, that there are rules in this tight-knit community, that one of the rules is to not smoke, that I had already betrayed my exclusion by not knowing.

Couldn’t I ask, though? Didn’t I feel my body lean towards them, magnetized by the unknown? By adventure? Didn’t I feel my tongue making out the words, making out my plea? But it was dust; my spirit bent, but I was afraid. And so I watched them pass, these mysterious men, into the darkness, towards wonders that I was not meant to see.

And me and the Russians, we left. We hopped a fence, walked quickly through some kind of construction site, and suddenly it was civilization again. I went to a kebab place, caked in limestone, and bought some fries. As I was going to the subway, I passed a book-seller on the street, and bought a book by the great novelist Amélie Nothomb to commemorate the occasion, Soif, or “Thirst”.

Was I quaffed? I had been in the catacombs. The illegal part, the real part. I had met people. This was one of my main goals in France, and I had done it, and I knew an entrance, I knew how. Didn’t I?

It was October then, and soon it slipped into November, then December. Every weekend, I’d wonder if I should go back to the bar, or back to the park. Every weekend, urgent things came up: a trip to Amsterdam, homework, a museum about porcelain, anxiety. They bled into each other.

For Christmas, my brother visited me. I’d gotten into the habit of looking up at the subway ceilings. We saw an enormous scarab beetle in iridescent greens and yellows, fifty feet long. “Look,” I said to him, “look up there. Balthazar painted that. He’s a cataphile. Isn’t that beautiful?”

At least I had that secret. The knowledge that everywhere I looked, there is a world, mysterious, but full to the brim with fractal life, just below the surface. That the themed bars live on. That if you meet the right people, they will say to you, Join us, if you crave for catacombs. That all you have to know is how to say oui.