I've always loved Korean books. I like to feel them, flip through them, handle them. They have nice paper. They have beautiful covers with flaps. They're durable and supple. They're cheap (the standard price of a paperback is about $9), but even the cheap books often contain color prints. The interiors are usually designed, with color accents and callouts and nice typography.

Despite my love for Korean books, I own nearly none, because I don't read Korean books, because I can only painstakingly read Korean. But I just got back from a trip to Seoul, the first time I've been since high school, and I picked up a copy of Han Kang's 2013 book of poetry 서랍에 저녁을 넣어두었다, variously called in English "I Put Dinner in the Drawer" or "I Put Evening in the Drawer" or even "I Stowed Evening in the Drawer". (The words for "evening" and "dinner" are the same in Korean.) As my luck would have it this is not a particularly great product of the Korean bookmaking industry, having a glossy rather than (my preferred) soft-touch cover, but the general cover design, as well as the book, is still pretty nice.

But more than the form, it's about the content, right? (This is what I must remind myself.) And the contents of this book are amazing. Unfortunately there is no English translation of the whole thing yet, though I do think there are scattered one-offs. As a personal exercise in improving my Korean (and my English), and because I didn't write anything else over my trip, I've attempted translations of the first three poems in the collection.

Translating poetry, especially Korean poetry, feels impossible. There's like three kinds of problems: the first is that I simply don't know that many words in Korean, nor do I know their connotations and associations; the second is that I don't know Korean literature and the tradition; the third is that Korean is full of little syllables that mean much, but that can hardly be translated at all.

어느 늦은저녁 나는 (Some late evening I)

Some late evening I was watching the steam rising from the rice in the white rice-bowl That's when I knew that something had passed me by forever even now forever is passing me by You have to eat I ate

Three challenges with this poem. First, what to use to translate "저녁", which is "evening" and "dinner". Second, how to translate the verb that Han uses to describe the steam, "피어올으다", which apparently is a pretty normal way to describe steam but to me suggests an image of steam flowering, which is beautiful, but doesn't fit with this poem. Third, the last two lines: "밥을 먹어야지 / 나는 밥을 먹었다". The word for "eat" is usually transitive and is usually used with "밥", which means in that context food, but also can mean rice, as it does in the fourth line. The sentence-modifying morphemes on these two lines are also complicated. The penultimate, in a low register, recalls a mother gently chiding her child that they must eat (which I like here and which I’ve tried to suggest), but can also be someone casually saying to themselves "Oh it's time to eat", or can be a neutral or positive declaration of resolve ("I'm going to eat", "I have to eat"). The last line emphasizes the subject "I" by its presence, when it’s normally dropped; how to put that in English, which always requires subjects. And that's not even to mention the extremely complex cultural resonances behind eating, which is partly what this poem is about, along with, like, the infrequent glimpses into the abyss that lies beneath the fabric of our daily lives.

세벽에들은 노래 (Song heard at dawn)

spring light and seeping dark through the crack a half dead soul faint i shut my mouth spring is spring breath is breath soul is soul i shut my mouth how long will it spread? how much will it seep? i'll bide my time when the crack closes i'll open my mouth if my tongue melts i'll open my mouth again yet again

This one is so pretty. An ars poetica, kind of. In my reading, it describes the gap between experience and the setting it down in words; at dawn the world of spirit meets the world of sense, which filters in through the cracks, at first ominous and then, we realize, everything in its place. The ability of the liminal transcendent to revive the soul. The ineffability of it. The hardest things about this poem was maintaining the rhythm of the final part, after the two questions, when there's this majestic crescendo of almost compelled or commanded poetic resolve, and, technically, the last two lines ("다시는 / 이제 다시는", or "again / now again"). While "다시는" does simply mean "again", the -는 suffix implies negativity ("It won't happen again"). And I don't really know what to do with that? Also the word I've translated "soul", "넋", does mean soul but is very rich.

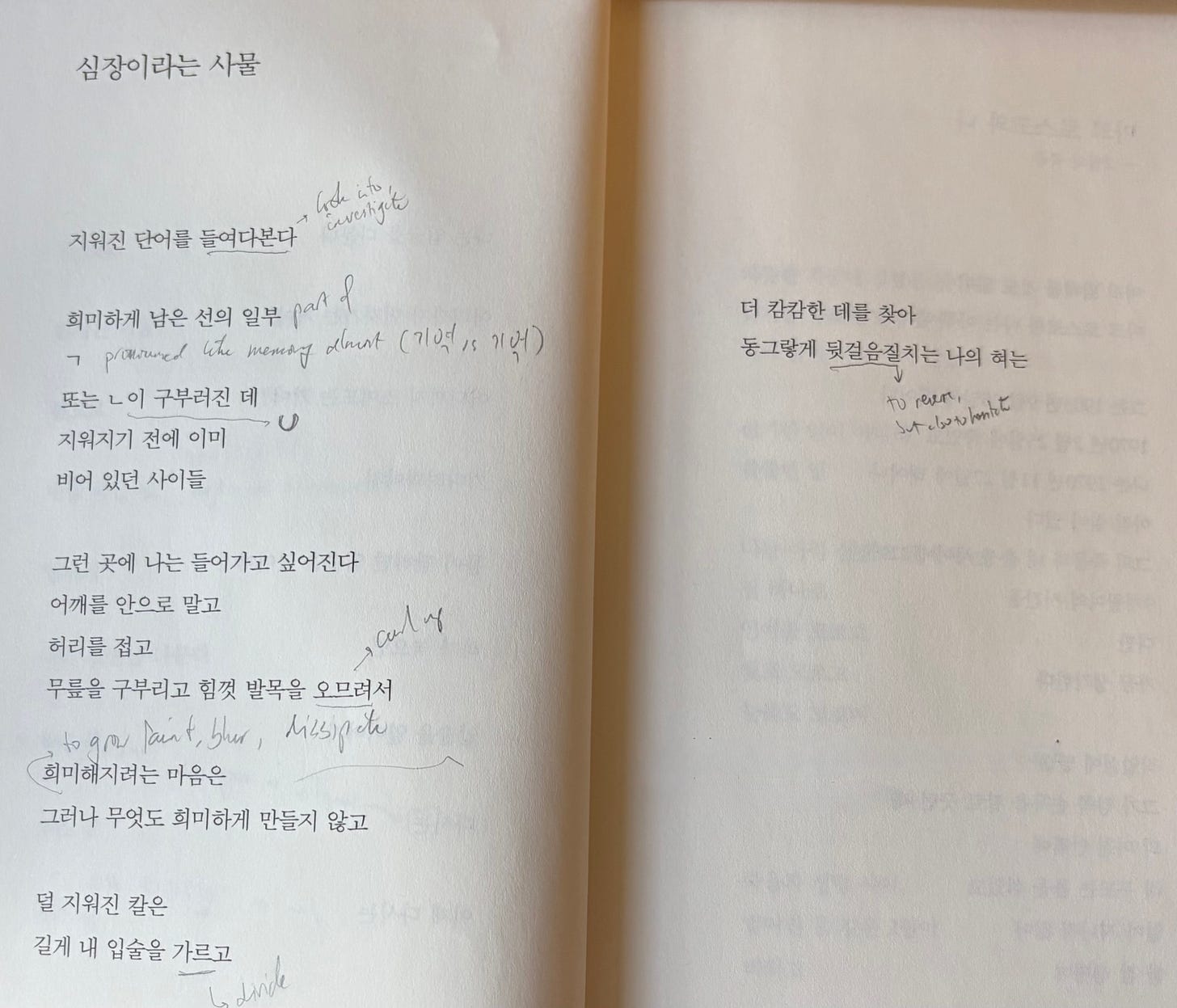

심장이라는 사물 (The thing called the heart)

I'm looking into erased words barely remnant lines n or where the u is bent places blank already before they were erased I want to enter them wrap my shoulders in fold my back bend my knees and curl my ankles tight And the will that grows faint yet does not itself blur anything And the half-erased knife widely parts my lips Searching for somewhere darker my hesitating round tongue

Yet again also nearly impossible, I mean, come on. The two letters I've replaced with "n" and "u" are "ㄱ" and "ㄴ". In my reading, the poem has a pun on these letters, as the pronunciation of the first sounds a lot like the word for "memory", and the second sounds kind of like the word for "you" (hence "u"). But when you put them together, they make a ㅁ, which sounds kind of like "마음", which means "mind" but less cerebral (as in "I changed my mind"), or, as I rendered it, "will" (but more emotional), or even "heart", as it's what carries your emotions (but "heart" is taken by the title, which translates a different word "심장"). If I used "nous" to translate it then I could've suggested the pun on "n" and "u" but "nous" does not fit at all with the register and strays even farther from emotion than "will" does.