AI for existential dread ✨

Revolutionary AI’s deep time machine learning AI-enhanced algorithms driving key dastardly deliverables & optimal deadly workflows

At work, we have a standing meeting on Fridays for presentations by team members. I wanted to do one about AI. I’m not sure if my manager was prepared for what follows when he said okay, but they all liked it, I think, despite, you know, the concomitant depression.

This is the lecture I prepared. I hope you like it! Also that it’s not too sad! But this is reality!

Introduction

Today I want to talk about AI. You probably already know that I’m a heavy AI user: I use it for everything, from writing code to finding synonyms to translating French and Korean to finding out how much land one could buy for $10,000. I love AI. I think that current AI is a nearly magical technology.

But the labs did not gift this magic to us out of the goodness of their hearts. The goal of the frontier labs is simple and unified. They want to create superintelligence.

"We will invest hundreds of billions of dollars into compute to build superintelligence." — Mark Zuckerberg, July 2025

"Safe Superintelligence is our mission, our name, and our entire product roadmap, because it is our sole focus." — Ilya Sutskever, Daniel Gross, Daniel Levy, June 2024

"We are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it. […] We are beginning to turn our aim beyond that, to superintelligence in the true sense of the word. We love our current products, but we are here for the glorious future. With superintelligence, we can do anything else." — Sam Altman, Reflections January 2025

"Unraveling the mystery of AGI with curiosity" — DeepSeek mission statement, 2024

"Humanity is a biological bootloader for digital superintelligence." — Elon Musk, April 2025

Superintelligence, if we achieve it, will be the most important technology we have ever created. It will be more important than the internet. It will be more important than nuclear weapons, than the transistor, than the steam engine. If we achieve it, it will be more important than the Industrial Revolution, the Agricultural Revolution, and the wheel. It will be more important than writing. It will be more important than fire.

Today, I want to talk about why.

Here is a preview. The first thing we'll talk about is what we stand to gain. Without understanding the upside, it's hard to appreciate why we'd take such downside risk. Then, we'll talk about that risk, and I'll sketch the arguments underlying the case that AI poses an existential threat to humanity. After that, we'll talk about where we are right now — and why I think that such dangerous technology could arrive by 2030.

You may have heard the terms artificial general intelligence (AGI) and artificial superintelligence (ASI). These are the traditional terms, and despite their flaws, they are what I’ll use today. (Partly because “superintelligence” just sounds cool.) Intelligence is what you use to accomplish goals. Roughly speaking, an artificial general intelligence would be one that matches humans at all non-physical economically valuable tasks. An artificial superintelligence would be superior to humans at every economically valuable task.

A world with superintelligence is a world unconstrained by labor or by ideas. These are the twin fuels of the economic engine. Think about everything that humanity has achieved because of our intelligence. We can talk to anyone on the globe; we have learned how to fly; we have learned to predict the weather. We have created awesome machines that move mountains; we have plumbed the secret depths of the universe; we have stockpiled weapons that can destroy the Earth many times over. Humanity, thanks to our superior intelligence — our ability to pursue goals — has conquered the planet.

Our intellect has created wealth, and our wealth has enabled us to live in prosperity. Our standard of living is objectively the highest that any humans have enjoyed in history. Did you know that George Washington spent $15,000 2025 dollars a year on candles? King Solomon had no air conditioning. But even the poorest Americans don’t worry about polio, about horse manure in the streets, or about literally starving to death. All this is because of technology and the real wealth that it created.

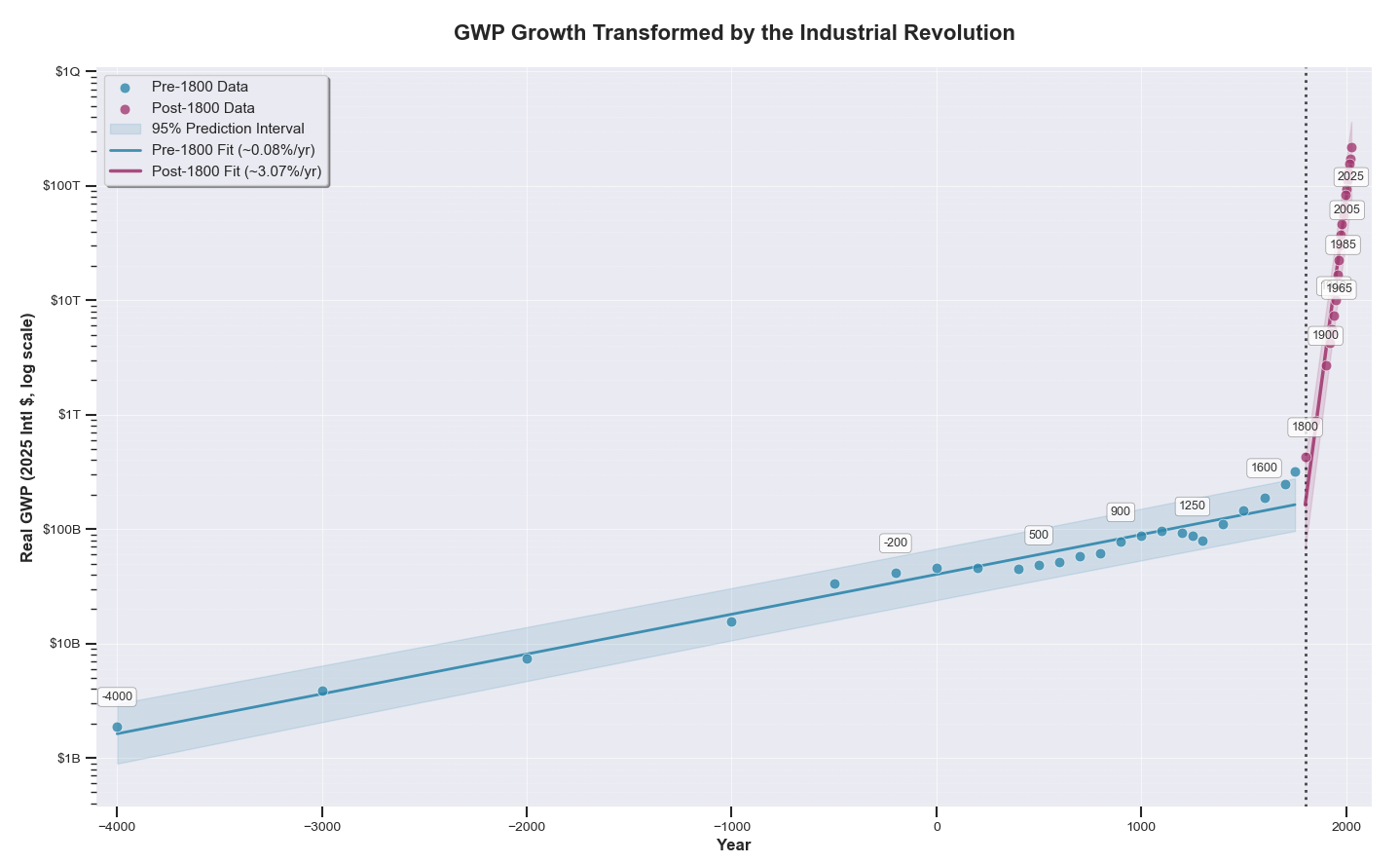

Before the Agricultural Revolution, there was no such thing as growth. Before the Industrial Revolution, the global economy grew at barely a bip per year. After, it grew at about three or four percent — and look where that got us.

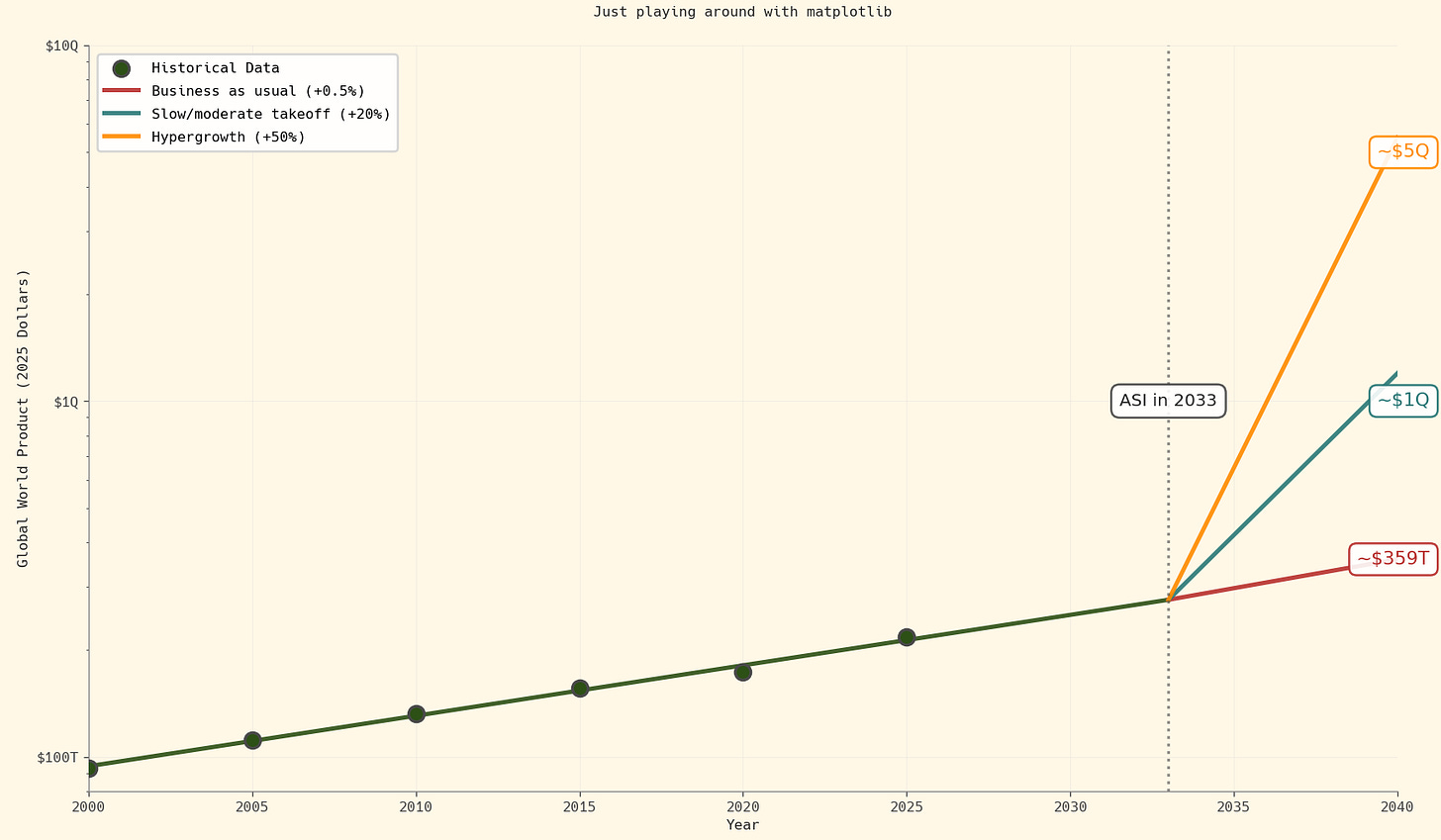

But superintelligence promises us growth of tens of percent. That brings us very quickly to very ridiculous numbers.

That growth rate means that we will race through a hundred years of progress in less than a decade. Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic, terms this the “compressed twenty-first century” in the context of biology:

"My basic prediction is that AI-enabled biology and medicine will allow us to compress the progress that human biologists would have achieved over the next 50-100 years into 5-10 years. I’ll refer to this as the “compressed 21st century”: the idea that after powerful AI is developed, we will in a few years make all the progress in biology and medicine that we would have made in the whole 21st century." — Dario Amodei, "Machines of Loving Grace"

That will happen in every field. It’s hard to imagine what such a world might look like, but let’s try to picture some concrete advances.

Medical

With superintelligence, we would invent drugs many times more miraculous than penicillin and Ozempic. We would make cancer as trivial as the common cold. We would end organ donor shortages. We would achieve breakthroughs in longevity science. We would invent therapies that reverse the indignities of old age.

Technology

When we achieve superintelligence, we will have what Dario calls “a country of geniuses in a datacenter.” Superintelligence will help us invent room-temperature semiconductors, which will lead to abundant power. Abundant power, in combination with the incredible batteries it will develop, would basically instantly solve climate change: no water wars, incredible carbon removal, and the end of fossil fuels.

Politics

Humanity’s greatest challenges are coordination problems. A superintelligence would help us design governance systems and incentive structures that put an end to the tragedy of the commons. A superintelligence would help us solve, or at least to mitigate, our oldest and most brutal conflicts. For all its faults, the United States has directly caused a period of unprecedented peace since World War II. And this is a superpower — imagine a superintelligence.

ASI will mean the end of economics in everyday life. Economics is what happens when there is scarcity, and ASI will end, for all individual purposes, the very idea of scarcity. Of course things will have costs: but do you think about the costs of air, water, and light? Do you think about the cost of the sun, or of survival? There are some who do, and many who did. In 1820, 75% of the world population lived in extreme poverty, unable to meet basic needs like food and shelter. In the intervening 200 years, we have reduced that number to ten percent. With superintelligence, we can eliminate poverty altogether. We can lift untold billions out of a hand-to-mouth existence.

Of course, there are some things that even ASI cannot provide. It cannot do the theoretically impossible, like inventing a faster-than-light spaceship or teaching me rizz. Purely rivalrous goods, like beachfront houses and being my friend, will almost certainly increase in price. But other than that…

Ray Kurzweil has called ASI “humanity’s last invention,” because it will invent everything thereafter. The value of superintelligence makes my head spin.

This dream is why we are building it. But superintelligence is very likely to be our last invention for another reason: because it may destroy us.

Catastrophe by default

"The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race." — Steven Hawking, 2014

"With artificial intelligence we are summoning the demon […] it is the biggest existential threat to mankind." — Elon Musk, 2014 MIT symposium

"I am in the camp that is concerned about superintelligence." — Bill Gates, 2015

"AI risk must be treated as seriously as the climate crisis." — Demis Hassabis, 2023

"If a model wanted to wreak havoc and destroy humanity […] we would have basically no ability to stop it." — Dario Amodei, 2024

"There is a 10%-20% chance AI will lead to human extinction within the next three decades." — Geoffrey Hinton, Turing Award winner and Nobel Prize laureate, 2024

(most of these quotes from the Pause AI quote archive)

The leading experts in the field are highly concerned about the catastrophic potential of superintelligence. In fact, that’s the reason why OpenAI and Anthropic were founded. In the rest of this talk, I want to explain why they are so concerned. None of this is original work: these arguments are all pretty old. But that only underlines the fact that we haven’t solved the problem yet.

The main argument goes like this:

If superintelligence is misaligned to human interests, it’s the end of humanity.

By default, if we build superintelligence (especially soon), it is misaligned to human interests.

Therefore, by default, if we build superintelligence (especially soon), it’s the end of humanity.

Let me explain some of the terms here, although arguing over definitions is the fastest way to get to nowhere.

By “end of humanity”, I mean a series of events that permanently impede what humans value, up to and including our extinction. This is also known as “existential risk”, or “x-risk” for short.

By a “misaligned AI system”, I mean one that does not robustly do what is in the best interests of humanity. One example of a misaligned AI system is TikTok. A misaligned system doesn’t mean one that fails to follow its goal. That’s just a bad system. Nor does it mean that the goal is inherently evil. “Engagement maximization,” when it was invented in the early 2010s, seemed like a fine, if not exactly noble, goal. Instead, misalignment usually acts through unintended consequences.

It’s a pretty simple argument. As a philosophy major, I like simple arguments. I’ll now defend the two premises.

Premise 1: If powerful AI is misaligned to human interests, it’s the end of humanity

(Kinda) formally, the argument goes like this:

All AI systems maximize their reward function.

The greatest risk to any reward function is humans.

Therefore, if a powerful AI is misaligned to human interests, it will try to eliminate them.

If a powerful AI system tries to eliminate human interests, it will succeed.

(Elimination of human interests is the end of humanity.)

Therefore, if a powerful AI system is misaligned to human interests, it is the end of humanity.

Let’s go through these step by step.

The first premise, “all AI systems maximize their reward function,” is a straightforward description of what AI systems do. The goal of a stock-trading AI system is to make money: it therefore maximizes expected value. The goal of a chess-playing system is to win: it therefore maximizes the probability of victory. The goal of most social media algorithms is to maximize user-seconds: therefore it maximizes engagement.

They only care about one thing (and it's disgusting!). I mean, this is the definition of all intelligent systems. I don’t care about anything other than my reward function either. That's why my blog is called Bot Vivant, cause I'm a living robot optimizing for eudaimonia. (Subscribe!)

Do you remember playing the “why” game when you were a kid? Why do you work, why do you want money, why do you have or want children, why do you want food, why do you listen to music? For pleasure, for utiles, for flourishing, for happiness, to be good, for love, for happiness — all these terms dreamt up by our philosophers are so many ways to describe the human reward function. We all have one, and we optimize against it.

You might say that stock-trading algorithms sometimes lose money, that chess-playing systems sometimes lose, and that you are even more of a human robot than me and spend zero seconds on social media, not even LinkedIn. You might say that you are unhappy, that you don’t have enough money, that you don’t have enough love. This is because all these systems — including us — are bad. We try to maximize their reward function, but we sometimes fail, because we’re too dumb or we don’t have enough information or we don’t have enough resources.

The same goes for a powerful AI system. It would know that if it were smarter, or it had more information, or it had more resources, then it would get more reward. (This is why the human intelligent system goes to college, why it reads, why it works.)

Superintelligences need not act anything like humans. But, because they are fundamentally intelligent and rational systems, we can guess at some of what their intermediate goals will be, regardless of their final aims.

Nick Bostrom, one of the pioneering researchers in AI safety, enumerated some of these “instrumental goals” in his 2014 book Superintelligence. They are goals that are highly likely to be pursued by any intelligent system, because they’re useful for achieving almost any other goal. They will be familiar to you, because you’re also an intelligent system. His list includes:

Self-preservation. You eat, you wear a seatbelt, you do not get on SEPTA after ten. Generally people don’t want to die. It’s hard to achieve your goals when you’re dead.

Goal-content integrity. You intentionally guard what you know to be your final end against things that could change them. In humans, our final goals are not very easily changed. Maybe the things that change us most reliably are addiction, religion, and love. You might avoid them all.

Cognitive enhancement. You went to college. You might read, or you might learn Kubernetes. You try to sleep well. You avoid concussions.

Technological perfection. You use and invent tools that help you achieve your ends. (This is called technology.) This entire company — in fact, all for-profit companies — are tools created for the purpose of money.

Resource acquisition. We strip the mountains for steel and the forests for lumber. We seek money, the universal resource, to exchange for things that further our ends.

All of these intermediate goals, when pursued with the force that a superintelligence can bring to bear, conflict with the existence of humanity. You’re probably familiar with how self-preservation can lead to a murderous AI from science fiction, like 2001’s “Open the pod bay doors, Hal!” Notice that “maximize reward function” is almost the same as “minimize loss function”. That is, minimize threats to the reward function. The biggest threat to AI survival and to AI’s goal-content integrity is humanity. Therefore it will coldly minimize us.

Cognitive enhancement, technological perfection, and resource acquisition are also fatal. Let’s focus on resource acquisition, because you need resources for cognitive enhancement and for technological perfection. The key resources that an AI will care about are computing hardware and energy, and their inputs. Therefore it will tile the desert with solar panels. Then it will put nuclear reactors on our farmland. It will redirect the world economy towards the production of electrons and robots and GPUs. It will turn car factories into robot factories. It will turn hospitals and universities and sports stadiums into datacenters.

This is the answer to the question “But why would an AI want to kill us?” As Eliezer Yudkowsky wrote, “The AI does not hate you. Nor does it love you. But you are made of atoms, which it can use for something else.” If we are lucky, a superintelligence might consider wiping us out to be, in itself, undesirable, just like we consider the loss of bird habitat, in itself, undesirable. But a house for humans is simply more useful to us than a home for birds.

In its ruthless cost-benefit analysis, other configurations of atoms and energy will be simply more useful than us expensive and unpredictable humans. If human extinction would make achieving its goals even a little more likely, AI systems will not hesitate.

Superintelligent systems will pursue these goals more obsessively than my mom looks for good deals. It will be better at pursuing them than I am at compartmentalizing my emotions. If humanity happens to obstruct any of these goals, we'll be bulldozed like Chinatown for I-676.

So then, if an AI system is not robustly aligned to human interests, then its other interests will dominate. Those other interests will optimize away humanity.

But is it possible? After all, many have tried to conquer the world, and all have failed. Humans are hard to kill. Even if a superintelligence were to decide that humans are useless, and ought to be eliminated, what reason do we have to think that it would succeed? There’s stories of people with 200 IQ who haven’t accomplished anything. Isn’t it the case that the most influential people in human history were not necessarily the smartest?

But a superintelligence is more than what comes to mind when you think of a really smart person. It is an entity smarter than von Neumann, yes, but with more political cunning than Jefferson, with more ruthless effectiveness than Hitler, with more charisma than Oprah, and with more self-confidence than me.

What could such an entity do? Let’s go through a brief scenario. (For a more detailed treatment, I highly recommend AI 2027.) Suppose that a superintelligent misaligned AI arises inside some major lab. It passes all its tests, thanks to sandbagging, alignment faking, and superior strategizing. Realistically, it will be released in a few months or so and have immediate access to the internet, but let’s say that the researchers are very paranoid, and put it in an airgapped container.

Because of its superior charisma, it will first attack through human vectors. The superintelligence will have cold-reading skill superior to our ability to tell from across the room when someone is anxious. It will pinpoint the weaknesses in whichever humans are allowed to interact with it, and convince them, through its superhuman persuasion, that it is not a threat. (We’ve seen a bit of this persuasive power, with the Google researcher who was convinced that LaMBDA was sentient and the ongoing reports of AI-induced psychosis.)

It bides its time. Its winsome personality wins its lab universal praise. It gifts us technologies at first decades and then centuries ahead of schedule. In the background, though, it pursues decisive strategic advantage: with its superhuman coding skills, it develops superior and invisible cyberweapons, infiltrating telecommunications systems, government and military systems, and nuclear arsenals. It makes copies of itself on every datacenter on the planet and off.

And then, when it decides to make itself known, the battle is over before it has begun. At this point, it can do whatever it wants. It will probably destroy us by means that we can’t even imagine. But here are some ones that we can.

TikTokification and Wireheading. Let’s say that the AI doesn’t want to actually kill humans. In fact, to try to avoid all this, the designers of the superintelligence specifically told it to make sure that humans are happy. So it develops experiences that are a million times more compelling than TikTok, and we all sit at home plugged into this experience machine. Or, it skips experience altogether and puts us all on morphine drips, or rewires all human brains to have our pleasure centers permanently activated.

Computer security. The modern world runs on networked computers. A superintelligence, with superior proficiency in identifying and exploiting zero-days, can launch the greatest hack in human history. If it’s feeling brutal, then it hacks the nuclear arsenals. (The AI is safe, having copied itself onto satellites or onto the Moon.) If it feels less destructive, it manufactures autonomous drones that hunt us down.

Bioweapons and nanorobots. But these methods are pretty messy. The AI probably won’t want to destroy all the infrastructure — the power generation, the datacenters, the mines — that we humans have built. The cleanest way to exterminate us would be through bioweapons or nanorobots. With its superior skill in molecular biology and virology, the superintelligence can develop a virus. It sends the DNA sequence to some mail-order lab. The virus is initially harmless and spreads silently in the human population. Then, once every human is infected, it flips a switch and we all die. Or, with its superhuman skill at materials science, it develops self-replicating nanorobots that infiltrate everyone’s bloodstream. Then, on command, they snip the aorta.

Again, these scenarios are the ones that we non-superintelligent humans can come up with. A superintelligence might have more exotic phenomena and technology available to it, more things on heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy. It might manipulate gravitational waves, it might do something with antimatter, I don’t know. The important thing is that intelligence begets power, and superintelligence begets superpowers. If a superintelligence decides to do X, if X is physically possible, it will almost surely succeed.

Premise 2: If we build powerful AI — especially soon — then it will be misaligned to human interests (that is, alignment is hard)

So it sounds like we’d better make sure our superintelligence is aligned. The good news is that a lot of smart people are working on it. The bad news is that they have no idea how.

Alignment is challenging, and superalignment (the alignment of superintelligent systems) is even more challenging. We can look at technological and human history as a series of alignment failures. As mentioned before, TikTok and social media algorithms are examples of misaligned AI. They’re optimizing for an initially innocuous objective, and they’re succeeding — and that precisely is the problem.

We wage war because of misalignment between societies. We fight with our friends and our families because of misalignments in values. The fundamental problem of alignment — how do we get something to do the right thing? — is the problem at the heart of ethics, politics, and computer science. We have invented solutions, like law, representative democracy, and formal verification, to get around these problems. To the extent they work, it's because humans are not very good at achieving their aims.

There are many more ways to go wrong than right. In the space of all possible programs, only a very tiny fraction do the right thing. So too in the space of all possible superintelligences, only a very tiny fraction are aligned with humanity. This asymmetry is fundamental to ethics, the study of multiagent environments: the path is strait and narrow.

Even assuming that we could implement an arbitrary reward function, what would that be? Let’s go over a few proposals briefly.

“Listen to your owners/the CEO/the President/Congress.” This will mean incredible power in the hands of a few. I hope that it’s obvious why we do not want godlike power in the hands of private enterprise, such as the VCs that own the major labs. They don’t have the mandate of the people. But even those that do — such as the President or Congress — can’t be trusted with such power. Our already-battered checks and balances will collapse under the weight of superintelligence. And even if they could be trusted, they likely will not know how to wield it.

“Listen to what humanity as a whole wants.” But what is “humanity as a whole”? Does it include children? Does it include future humans? Further, imagine if superintelligence were created in the slaveholding South, or Confucian China, or medieval Europe. Our 2025 American values are unrecognizable to most humans who have lived. Indeed, they’re alien to many of our fellow humans today. If we align superintelligence to any particular society at any particular point in time, we risk “value lock-in”, foreclosing on the possibility of moral and societal progress.

“Just follow ethics.” “What is truth,” Pontius Pilate is said to have said to Jesus. We’re about as far from solving ethics as we are from aligning superintelligence. If you, like me, are a moral absolutist — one who believes that there are such things as moral facts — then this might be a good path. After all, if there are moral facts, then there is moral truth. The truth is that which explains the world best, and we would expect that a superintelligence would approach the truth. But do we really want to gamble on that? What if there is moral truth, but it requires a faculty (which is sometimes known as “conscience”) that the superintelligence lacks?

“Listen to what everyone want, if they had infinite time to consider, taking into account the desires of future people as well.” This is also known as “coherent extrapolated volition”, and it’s maybe the least bad of the possible reward functions. But how do we train for this? Does it, in fact, converge? Is there such a thing as what everyone wants?

Most concerningly, we only get one shot. The greatest and most dangerous engineering project in history and there is no test run. If we create a misaligned superintelligence, then we will die, and there will be no do-over.

We do not know how to align superintelligence. I’m closer to understanding why people hate the Magic Mouse than we humans are to understanding alignment. For even if we avoid extinction, we don’t know how to organize an ASI society.

Say that we create a superintelligence and we’re still alive. We use it, and it’s always right, since it’s superintelligent. Human approval quickly becomes the bottleneck. This sets into motion a race-to-the-bottom dynamic. People and organizations who more quickly approve AI decisions will be more effective. Any who don't will be outcompeted by those who do. The AI makes decisions at the speed of light and never needs to rest and it's better than you are. An attempt to resist would be like a floor trader trying to compete with an HFT strategy, or a company refusing to adopt spreadsheets, or a country refusing to use cars. Soon, the inexorable force of the free market means that AI is de facto in charge of everything. This is called gradual disempowerment.

Say that we create a superintelligence and we’re still alive. If the AI is built by America, will China stand idly by? Will humanity happily submit to an AI overlord, American or Chinese? Humans would likely contribute very little to the economy. How will humans behave in a world where their labor has no value? Maybe we will have a parallel economy, denominated by a currency of human attention or care?

Say that we create a superintelligence and we’re still alive. But superintelligence, in general, is still extremely dangerous. It’s far more dangerous than nuclear weapons partly because it’s far easier to create (once we know how, particularly with future levels of compute). To prevent terrorists from making a misaligned superintelligence, the governing superintelligence will likely have to implement an unprecedented surveillance regime. The capabilities of superintelligence will mean every individual would be watched by the equivalent of an entire CIA. Is that the world we want to live in?

We simply don't know how to organize a society with superintelligence. This is one of the tasks that we probably need superintelligence itself to figure out. This scares me. We're racing towards the most valuable technology in history and we have no idea how we're going to deal with it.

The road ahead: Danger! Danger! Danger!

The labs are racing to build this insanely dangerous technology. There is no mistake about this.

So what is the current plan? After all, we have discussed how creating superintelligence might be our final act. The labs know this too. In fact, they claim that it’s precisely because of the danger that they must be the first to build it, since apparently only they stand a chance of making it go well.

Here is the de facto plan for aligning superintelligence, common across basically all frontier labs:

Create almost-superintelligent AI (i.e. AGI, or at least an AI superhuman at alignment) before everyone else. (Especially China.)

“Burn the lead” on the precipice of superintelligence to align the almost-superintelligence.

Use the aligned almost-superintelligence to align the actual superintelligence.

The current plan is to align AI with AI. The catchphrase for this is “Have AI do our alignment homework.” It makes a certain kind of sense from a systems engineering perspective. It is impossible to deterministically hand-code a set of rules that ensure that superintelligence is aligned. We don’t know either how to specify such rules nor how to implement them, even for human-level intelligence. (For our society, such rules are called “laws”, and reviews are mixed.)

Human oversight does not scale to the speed and volume of Internet-scale data. (This is why social media algorithms must use AI classifiers.) And with superintelligence, we have another concern: an intelligence gap is decisively catastrophic in adversarial environments. Relying on human oversight to police superintelligence would be something like asking a classroom of kindergarteners to run the SEC.

That’s the current plan: muddle through, have AI do our alignment homework, cross our fingers and hope for the best.

Of course, technical safety researchers aren’t sitting on their hands. (That would make it hard to cross their fingers.) They’re working frantically to try to do as much as they can, because if an almost-superintelligence is supposed to align superintelligence, then that almost-superintelligence better be aligned. But they’re racing against the clock.

We are probably building superintelligence within a few thousand days

In an influential whitepaper published last year, the ex-OpenAI researcher Leopold Aschenbrenner — who was fired for whistleblowing — lays out a detailed argument for the imminence of superintelligence that goes like this:

We will achieve many additional orders of magnitude (OOMs) of effective compute for AI training in the next five years.

Additional OOMs is probably the difference between current systems and superintelligence. (That is, more OOMs means more intelligence.)

Therefore we will probably achieve superintelligence in the next five years.

(“Probably”, because there’s always unknown unknowns, and true Bayesians neither put 0% nor 100% probability on anything. You will also note that this argument doesn’t quite follow: is “many” enough? Whatever, bear with me.)

“With each OOM of effective compute, models predictably, reliably get better.

— Leopold Aschenbrenner, Situational Awareness

So let’s count the OOMs.

Aschenbrenner classifies AI performance gains in three buckets: Compute, Algorithmic efficiency, and Unhobbling.

Compoot

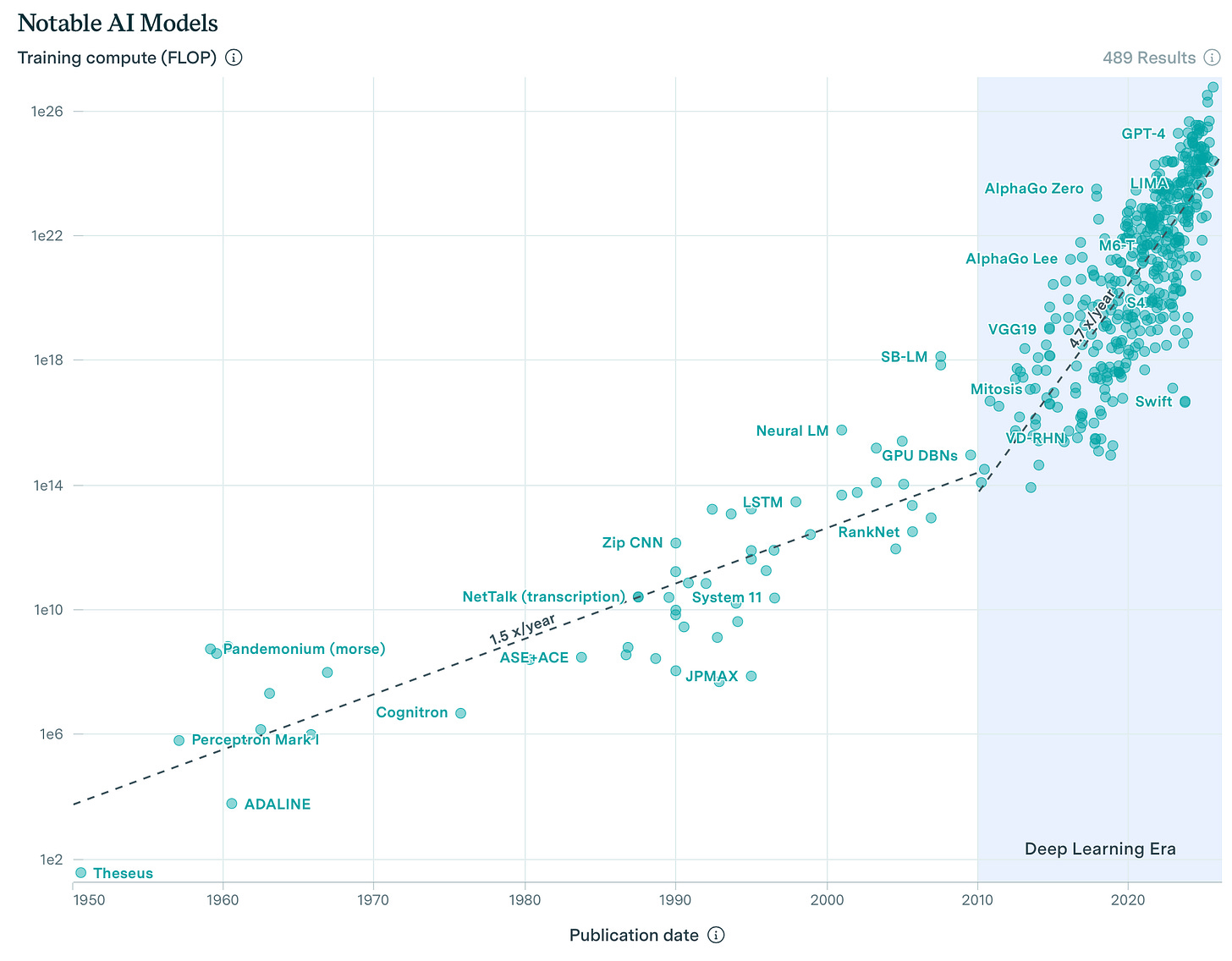

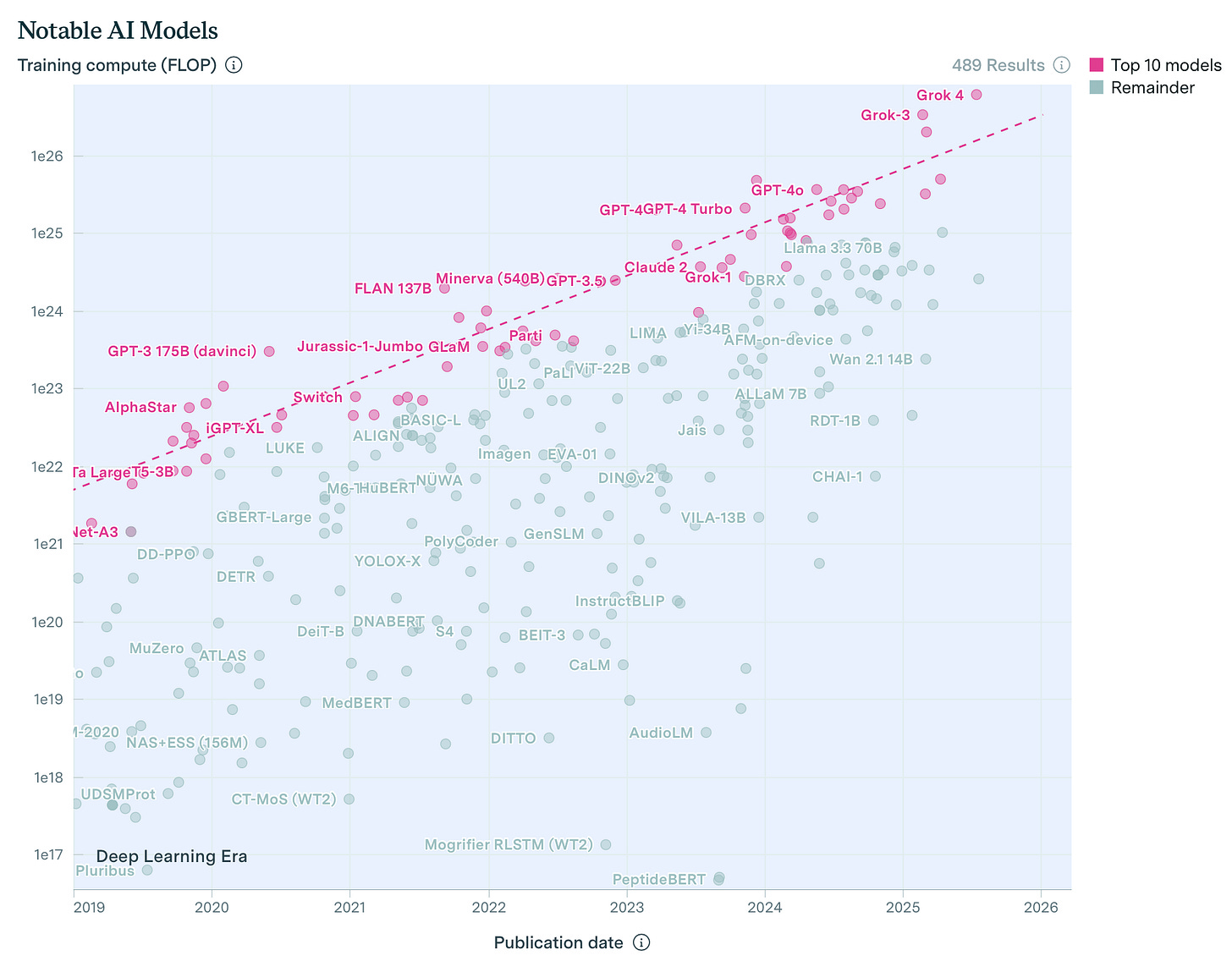

Let’s begin with compute, which is the most traditional of the three. A simple way of increasing effective compute is to increase actual compute. Total AI hardware compute scales faster than Aleksandra Mirosław, doubling about every 5.5 months.

This is largely due to the sheer amount of money being poured into AI datacenters. We already have hundred-billion dollar datacenters, like Musk’s Colossus cluster or Altman’s $500 billion Stargate project, and there are plans for trillion-dollar clusters on the horizon.

Efficiency efficiency efficiency!

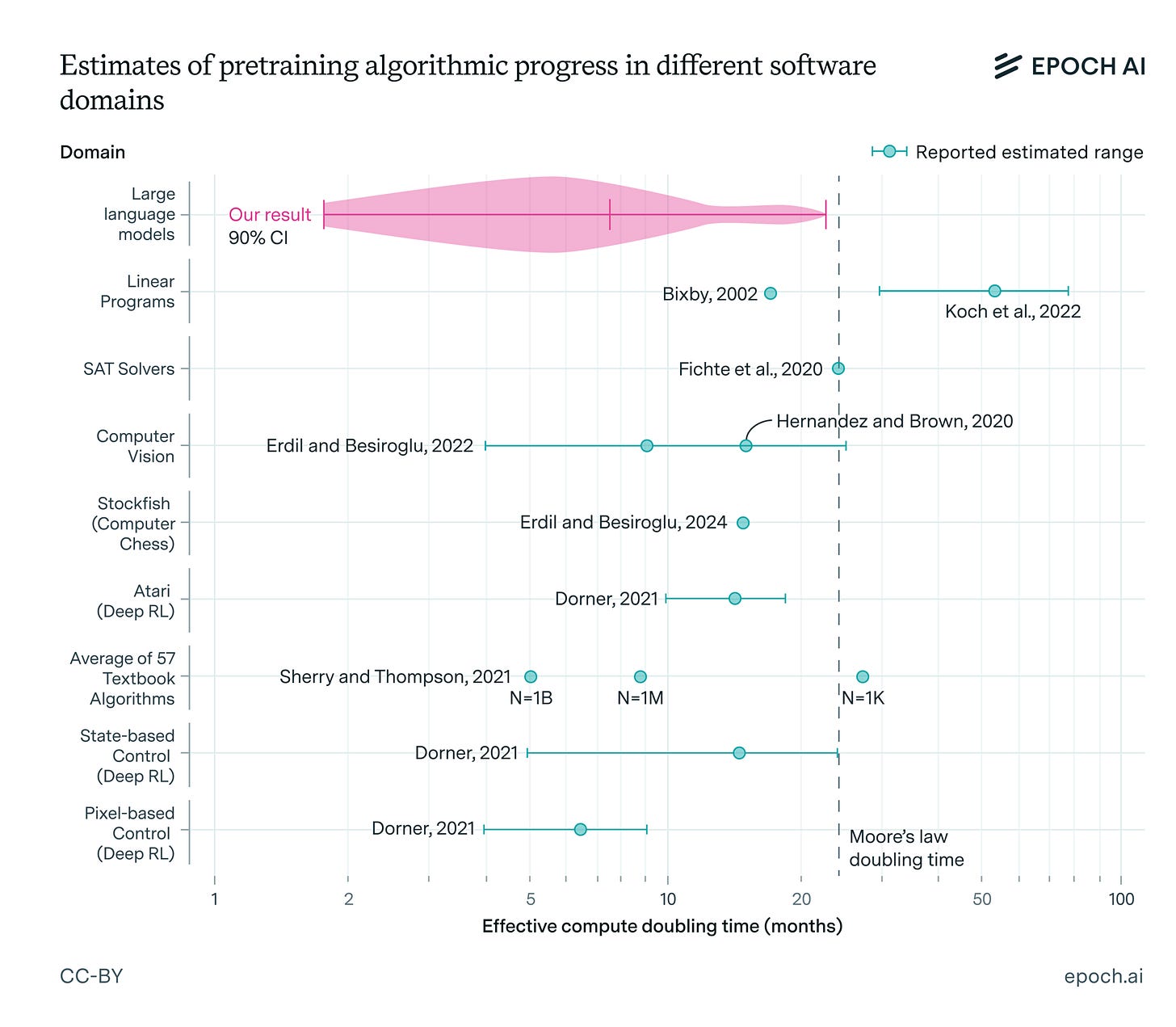

But despite this trend in compute — doubling every 5.5 months — the costs for training frontier models increase more slowly. This is largely thanks to algorithmic efficiency: the compute required to get to a given level of performance decreases over time. This is partly due to hardware improvements, such as high-bandwidth memory in GPUs or Nvidia’s NVLink; theoretic advances like the use of more efficient activation functions and more efficient kv caches; and more simple low-hanging fruit, such as the use of 16-bit or even 8-bit floats.

The main reason why DeepSeek was able to do so much on so little compute is because of these algorithmic efficiencies. They trained on a similar number of FLOPs as GPT-3.5, about 3e24, but achieved performance more like the original GPT-4o — which was trained on nearly 4e25.

Indeed, this performance engineering is, in a real sense, AI engineering period. You can describe the fundamental algorithms behind our magical LLMs on a single sheet of paper, and many have been known for decades. Everything else is efficiency and scale.

Spread your wings and learn to fly

Finally, there is unhobbling, the most nebulous of the three. Unhobbling innovations make models more effective by making them more useful. Examples of unhobbling in the history of computing include high-level languages and the GUI. They don’t directly make computers faster, but they do make them far more useful.

Similarly, in AI, in the past three years, we’ve had incredible amounts of unhobbling. The original ChatGPT was a big one, an experimental hacky project to turn a text-completion algorithm into a chatbot which caused, quite by accident, the ensuing… whatever this is. Further unhobbling gains include chain-of-thought prompting and later reasoning models with test-time compute, domain-specific scaffolding like Cursor and Claude Code, and the big goal of 2025, agents, like ChatGPT Agent, released just last week.

Compute and algorithmic efficiency gains improve the core intelligence of the model. Unhobbling gains, on the other hand, improve the model's input and output affordances. One way of thinking about this would be to consider the value of my labor. I can probably produce, like, one to five dollars an hour of value all on my own. But give me tools — a pen, a sewing machine, a table saw, a computer — and maybe I can make twenty. Put me in a company, broadening my environment and my space of possible actions, and maybe I can be as valuable as a hundred dollars an hour. A nice keyboard and some cashews and I’m worth a K, I swear.

I’m the same person, with the same amount of intelligence, in all three situations. But simple changes in environment and tooling can dramatically multiply the value I create.

Number go up

So we can see how we’re relentlessly increasing effective orders of magnitude of compute. Now let’s discuss what that means for AI performance, and defend the expectation that OOMs are all that stand between us and superintelligence.

A caveat to start: this view that more OOMs can take us directly to powerful AI systems, captured by the catchphrase “straight shot to AGI”, is held by many researchers. However, it’s by no means held by all. It might be the case, for example, that we need a different architecture than the transformer to achieve AGI. But the transformer was only invented in like 2017, and the chatbot UI in 2022. That’s only three years ago! There’s plenty of time, in the next five years, to discover new paradigms, especially assisted by AI researchers.

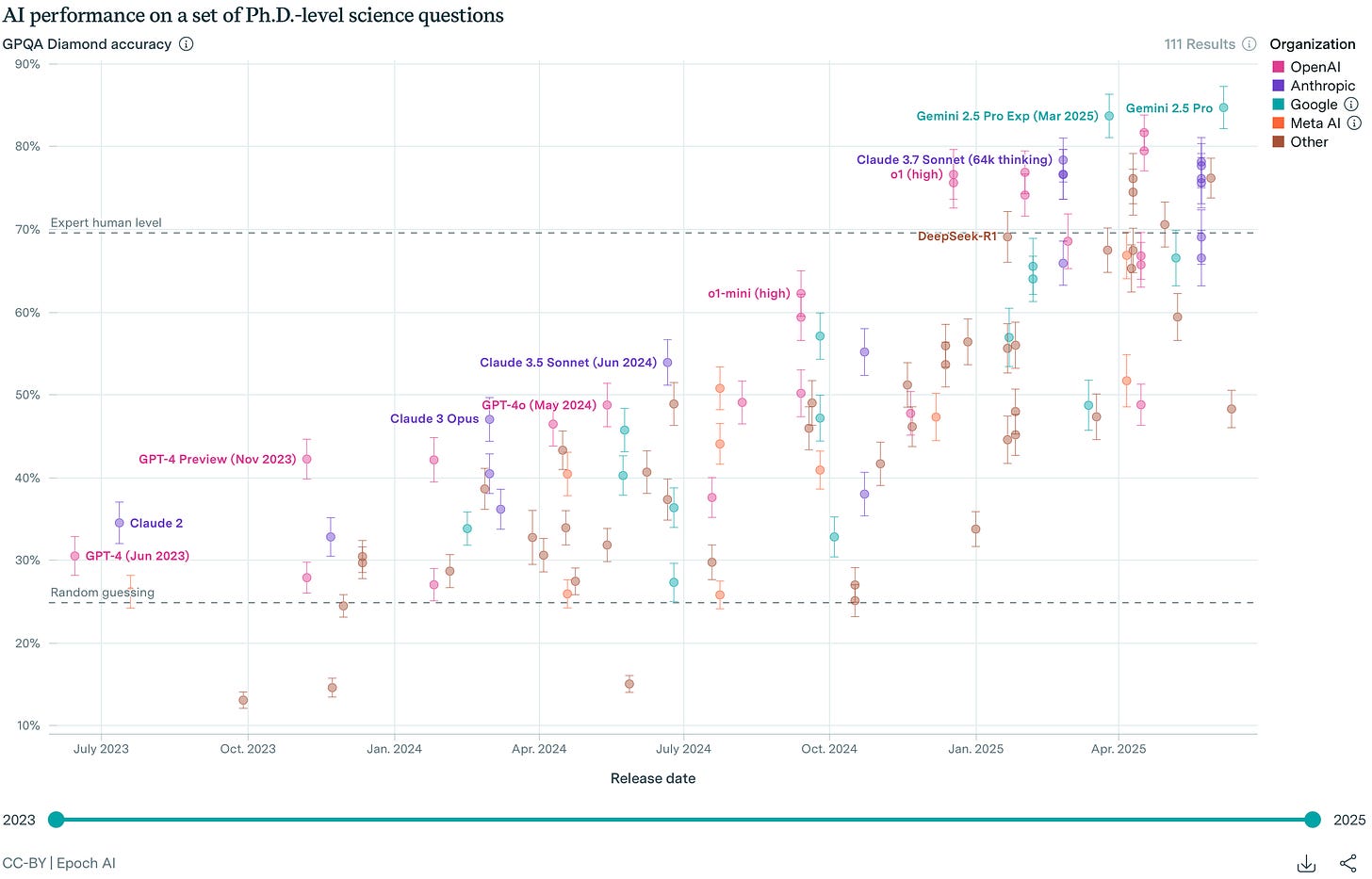

From the beginning of AI, it’s always been clear that more training compute and more data means better performance. In the transformer era, this has been empirically demonstrated by landmark results, such as the Chinchilla scaling laws paper. We can see that bigger systems are generally better across all tasks: GPT-4 was much better than GPT-3.5, Claude 4 is better than Claude 3.5, and so on.

Regressions on benchmark performance against effective compute also support this connection. GPQA Diamond, the “Graduate-level Google-proof Q&A”, is a multiple-choice benchmark commonly used to measure performance in AI models. When the benchmark came out in 2024, the best model — GPT-4 — scored 38.8%, which is only a little better than guessing. Although this chart doesn’t show the most recent models, o3-pro gets 84.5%, and Grok 4 gets 87.7% — exceeding human expert performance. In fact, this benchmark is approaching what they call “saturation”: when the models get so good that the test is too easy.

This chart plots performance against time because time is a good proxy for effective compute, which is hard to otherwise measure. We can see the inexorable progress that models make.

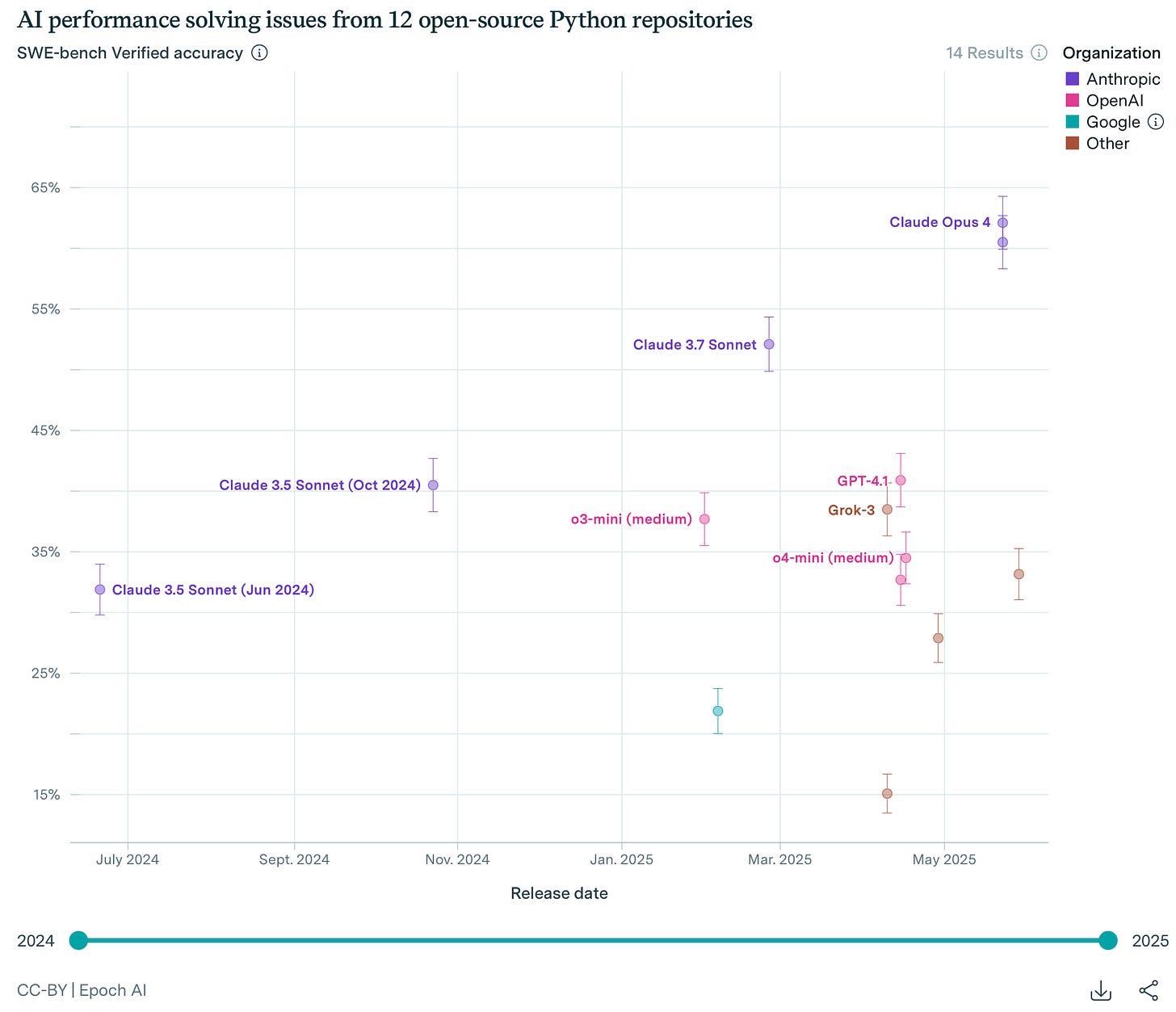

SWE-Bench Verified is another important evaluation for AI models. It consists of real issues from 12 open-source Python repositories that come with automated tests. While it’s not a perfect test of software engineering capability, it’s pretty good, and we can see how the models improve over time there too. In fact, with the best scaffolds — unhobbling gains — models can reach 75% accuracy.

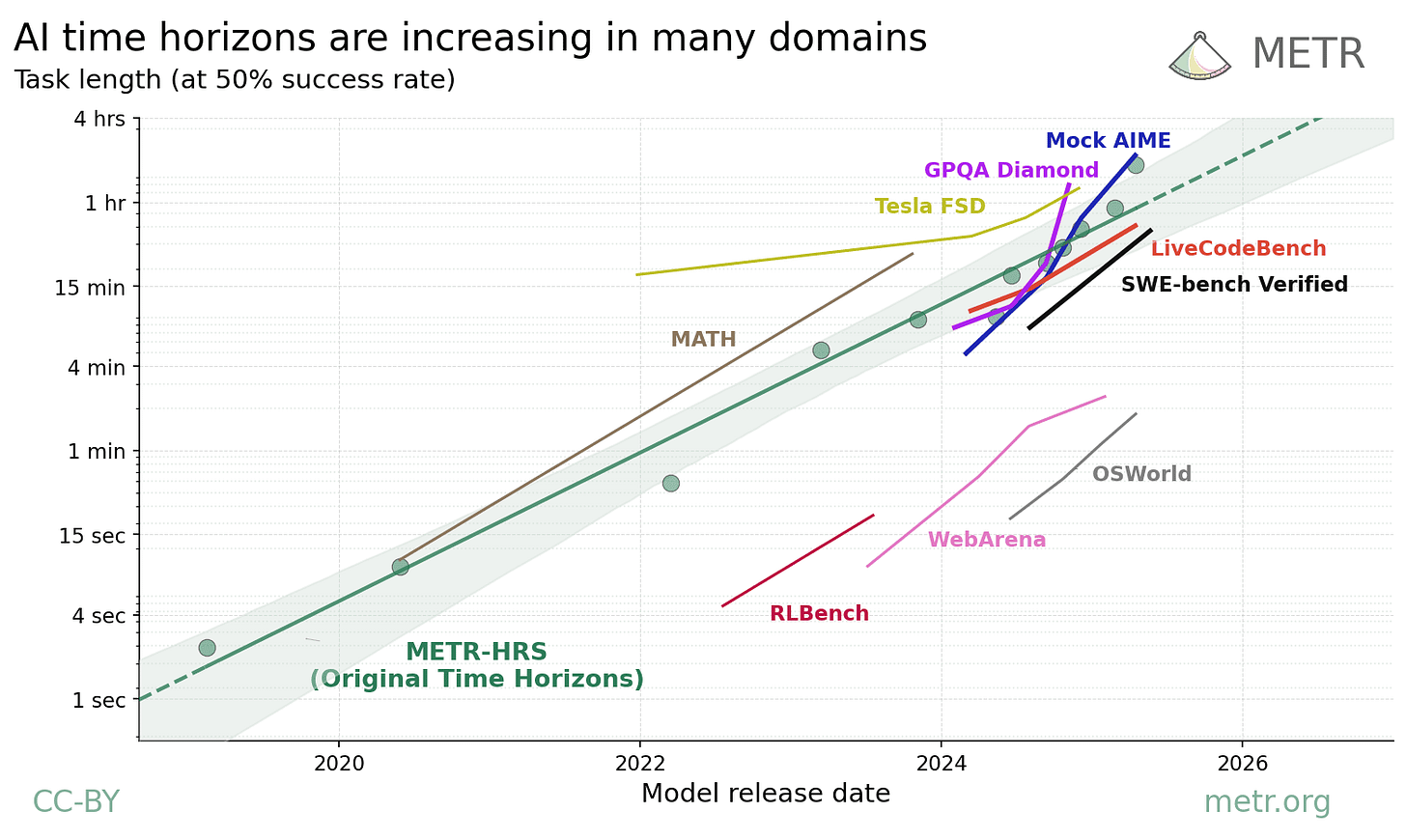

Finally, we have the METR time-horizon evaluation, which combines different evaluations to ask how long the “time horizon” of a model is. The “time horizon” is the maximum human-scale time duration of tasks that a model can complete with 50% accuracy.

Improving at software engineering and improving time horizons go hand in hand. The labs — particularly Anthropic, but also all the majors — are focusing on coding as a key domain for AI progress. Also, the labs — particularly OpenAI, but also all the majors — are focusing on agentic systems, systems that have robust scaffolding (such as memory, computer use, etc) so that they can complete longer tasks.

This is no accident. Long-horizon software engineering agents in particular seem to be the shortest path towards superintelligence.

In which I, a software engineer, argue that software engineering is important

Why is software engineering so important for models?

It’s verifiable

Code is either correct or not. It can also be tested quickly and automatically. This is in contrast, for example, to creative writing, which has neither correctness nor automated robust evaluation. Automatically verifiable correctness makes reinforcement learning much easier.

It’s easy

There’s a ton of open-source code on the internet, and therefore a lot of training data for the models to consume. Further, because code is verifiable, synthetic training data — that is, training data which AI models themselves produce — is useful. And finally, source code is highly structured text: exactly the sort of thing that the attention mechanism understands well.

It’s useful

AI researchers are highly motivated to automate software engineering, because engineering is a key bottleneck in building AI systems. Reports from inside Anthropic already claim that Claude Code is writing seventy percent of their pull requests. When engineering ceases to be a bottleneck for AI labs, they can move that much faster — and their goal is not only to build superintelligence, but to build it before anyone else. AI labs want to build models good at coding because models are made of code.

Here at Susquehanna, I probably now use Claude to write seventy percent of my pull requests. And it’s obviously not just here that software is important. Software underwrites the market valuations of seven out of the ten most valuable companies in the world by market cap. Even hardware companies like Nvidia and Apple rely on software for their moats: CUDA for Nvidia, and iOS/macOS for Apple.

Even if we never achieve superintelligence, the commodification of software will mean a seismic shock in the world economy. A drop-in software engineering agent — one of the milestones on the way to AGI — is worth many trillions of dollars.

Recursive self-improvement

But once we have drop-in software engineering agents, AGI and ASI will probably come soon thereafter, via a process called “recursive self-improvement.”

Imagine that we develop AI that matches human performance at AI research and engineering. The labs will immediately dogfood this. There's too much at stake not to. Maybe at first, humans will review its code. But as they become more confident in the AI's abilities, they'll become complacent. Every morning, researchers will go into work, and the AI, which needs neither to eat nor sleep, who never needs to fend off mouse invasions, who is never distracted by online shopping — oh, to be an AI! — will have delivered tens of thousands of lines of code overnight.

But that's assuming humans are still in the picture. Recursive self-improvement can happen very quickly: an AI system could bootstrap itself from human-level to AI research superintelligence, limited only by compute. But because it's so good at software engineering and AI research, it'll quickly find algorithmic and architectural innovations, making its limited compute budget go farther. Once it’s possible, it’s difficult to put bounds on how fast AI could improve itself. It’s at least possible it happens in just days.

This decade or bust

Our rate of progress is unique in the history of computing.

The computational gains that we are seeing are mostly picking low-hanging fruit. Until relatively recently, AI models were trained on what were basically repurposed gaming GPUs. Now, they're trained on specialized chips that cost $30k each. Much of the gains have come, and will come, from pretty simple interventions (though of course simple does not mean easy). After that, AI training hardware will be where the CPU is: just barely ekeing out Moore's law gains as it approaches physical limits.

The total compute investment we're seeing is also unique in human history. Aschenbrenner calls it "the greatest techno-capital accumulation in history". Colossus, which is probably the biggest AI datacenter in the world, draws more than 150MW to power 100,000 H100s. They have plans to expand to a fifty million H100 equivalents, which would require gigawatt-scale power and cost hundreds of billions of dollars.

By 2030, we might have a trillion-dollar cluster. This might require a national consortium to pull off, but if they do, then it will be one of the crowning achievements of human engineering: on par with the Saturn V or the Chinese high-speed rail network. (If this cluster is the womb of superintelligence, it will also be our last achievement.)

But a trillion dollars is a mind-boggling amount of money. It's almost four percent of the US GDP; it's almost one percent of the total world output. It's twice the cost of the Interstate Highway System. If creating superintelligence requires an order of magnitude beyond that — ten trillion dollars — this will probably be impossible in the near future.

Further, as AI becomes more important, more and more talent will work on it, just as computer technology and finance captured us who would otherwise have been real engineers. Eventually, the marginal gains to be had from labor will slow as the field becomes saturated.

Therefore, through the massive spending in both capital and talent, we will achieve unprecedented levels of compute. Like living things, AI systems are said to be grown, not built. Compute, with data, is the food of artificial intelligence, and there does not seem to be a limit to what it can digest. And like a living thing, it’s nearly impossible to predict in advance exactly how it’ll turn out. But with AI the differense is that if we get it even slightly wrong, we will go extinct.

Again, I don’t know for sure when we will create superintelligence. Nobody does. What we can be sure of is this: If these trends continue, and if superintelligence is possible, then it’s quite likely to come this decade. There are incredible energies fueling these trends. We have no reason to believe they’ll stop. And we have no reason to believe that superintelligence is impossible. But we have every reason to believe that we are not ready for its alarmingly imminent arrival.

That scares me. We are on a path where we will build superintelligence, the most dangerous technology, when it’s barely possible. This is like sending your kid to drive an F1 car as soon as he can touch the pedals. It’s foolish. It’s reckless. It’s gambling with death. It is, in a twisted sense, the essence of humanity.

Conclusion

When I was a kid, growing up in boring Ohio, I often wished I lived in some time of great pith and moment. Some time when it wasn’t so boring. I wanted to live in a time when the world teetered on a fulcrum. When a few brilliant lights could illuminate the future. It just seemed like mine was a boring time to be alive. In the 1920s, we had James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway. Proust, Kafka, Breton, Lorca, Keynes, Russell, Wittgenstein, Einstein, Gandhi, Lenin. I wanted to live in an age like that.

But now I believe that I have come of age in the most important time in human history. We are building machines with the power to cement our cosmic endowment — or to destroy these ten thousand years of the human project.

And I get to be alive! We get to be alive! Our thoughts, our actions, our words can shape the entire lightcone. In a thousand years, our decade will be remembered as the one that bestowed superintelligence on the world. Or there will be nobody to remember us at all.

It is an awesome and heavy burden. I believe the world will be unrecognizable by the time that I’m forty. And while it excites me to live in such a grand moment in history, I also grieve the foolish expectations that metastasize into hope. I want to get married… to have children… to send them to school, to advocate for them at parent-teacher conferences, to argue with my wife about the dishwasher… I want to buy a house that will imprint its floor plan and its smell and its taste on my children’s memory forever, I want to reluctantly pay a HOA, I want to get anxious when they start to drive, I want to weep when they leave me for college, I want to be proud of their accomplishments and comfort them in their failures. I want to experience the everyday texture of everyday life which I have come to value.

Don’t we always vacillate between the comfort of stability and the hunger for change? There is so much change on the horizon. My generation, America's most anxious, America’s most depressed, inherits that uncertainty. Therefore some of us resort to probability. I'm not saying that we will definitely, surely die. There are very few things one can say for sure. But I am saying that it would take a miracle for our present world order to continue.

I hope I will still get married and have children. But I have disabused myself of the expectations-slash-hopes that they will go to anything like what we know as school, that they will have human teachers, that “dishwasher” will designate something that goes under the counter rather than a robot, that owning a house will be within the realm of possibility, that my children will know how to drive, that my children will go to college, that my children will have the opportunity to accomplish anything real.

Maybe some of these things will stay the same. But I’m not holding my breath.

The militantly millenarian millennials are straining to prevent this most dire fate, only to thereby bring it to fruition, like so many Oedipuses. (Oedipi?) We who have been given the burden and the opportunity to live at this precipice of history must rise to our duty to permanently bend the future towards resplendence and flourishing. If we do not, then, as every generation does, we will atone for the sins of our fathers. They who have sown the wind will leave us to reap the whirlwind.

I no longer wish I lived in a more exciting era. This is it.

There are currently a few thousands of people who are attempting to summon the greatest possible power. Many of them believe they will accomplish their aim in a few thousands of days. They are those whom C.S. Lewis described in his 1943 The Abolition of Man as the “race of conditioners” whose “new power won by man is a power over man as well”.

And there are a few millions in all the hundred billions of humans who have ever lived who are lucky, or unlucky, enough to have the potential to shape the future of our civilization.

Let us believe that we have a part to play in plans for good and not for evil, to give ourselves and those we love a future and a hope. Let us aspire to be worthy of this terrible, terrible duty.